Cookie’s gotcha day is coming up soon, marking a year since his strange mixture of softness and neediness entered my life. It’s hard to think about my time before him. Zach and I talk a lot about how it feels like it’s been longer than a year. We can’t conceive of a time in our life when he wasn’t staring up at us demanding affection or a bite of whatever we’re eating.

I didn’t think I would ever actually get a dog. I tried it once and failed miserably at it. The experience of that failure got me to the lowest point in my depression I’ve ever really been at and I spiraled, assuming that would happen again.

Also, I had some past baggage with raising a dog with a partner: having (in my mind at least) helped my last ex raise his dog from a puppy. I grew an attachment to her, more so than I probably should've, and when our relationship ended the sudden loss of her from my life also stung in a way I haven’t been able to fully articulate since it happened.

A credit to his character, he did offer to let me see her whenever I wanted. I tried it once but knew it wasn’t a real solution. I wanted to be the type of person who could easily get over something (or someone), but I wasn’t. The loss I felt was monumental, the grief and shame and anger all mixing with the good stuff. She was tied to him just as he was tied to her and, weirdly, she was tied to us or whatever vision of that I had in my head at the time.

I knew the only way I was going to recover and not sink into some horrible version of myself (though I probably did that too) was just to cut off any connection, even if it hurt.

And then I got better. Or I started getting better. I kept going to therapy. I took my medicine. I tried to separate myself from the feeling of failure that came with the end of a relationship. I kept looking at dogs because I thought I was ready. Then I adopted one because I thought I was ready.

Truthfully, I wasn’t ready.

I've been training Cookie off and on. He gets some things really well and others it takes a lot of time. I’ve had a lot of success with using a clicker, particularly with loose-leash walking.

Clicker training follows the laws of classic conditioning, first discovered by Ivan Pavlov in his experiments with dogs. First, you associate the sound of the clicker with a reward. This is referred to as loading the clicker. You click and give a treat. Click and treat. Click and treat. Eventually, you’ll build up a strong response where clicking will immediately signal to your dog to look for a treat, even if none is present. This usually takes about 10-20 treats but varies, depending on your dog. Once you’ve achieved this you can use a clicker as a mark a term dog trainers use to mean the signal your dog looks for when he’s accomplished something you want him to.

The training process can be hard, but with a little dedication and a lot of practice, you can condition most dogs to do what you want.

Classical conditioning was the beginning of behaviorism in the psychological field. By understanding this conditioned response in animals and applying it to humans, psychologists were better able to understand how we train our own brains to outside stimuli.

If you’ve ever been in therapy for anxiety you’ve likely done something similar, though in reverse. Cognitive behavioral therapy focuses on eliminating negative thought patterns that often lead to a cycle of anxiety and depression. In these therapeutic settings you’ll likely practice some form of talk therapy and association. For me, at least, I focused on associating the negative thoughts I was having and reframing them to be something positive. It sounds cheesy and a little annoying, but it works.

It takes time and a lot of practice though. It’s not enough to understand where the emotion or signal is coming from, you have to do the mental and physical work to retrain the brain. Bad thought, repeated good thought. Bad thought, repeated good thought. Bad thought, repeated good thought.

On the most basic level, it’s not that far from a clicker.

When Zach brought up the idea of getting a pug, I was hesitant. I told him about my fears of getting a dog and the past parts of my history that made me nervous. I fretted over it a lot. I worried:

I wouldn’t be ready.

I wouldn’t be able to take care of a dog.

Something bad would happen to them too.

We would break up and I’d have to lose another dog..

The first dog I had I never took care of1, the second dog I had I said goodbye to, and the third dog I took care of I abandoned. I didn’t want to fail again. I didn’t think I could take it.

I talked to my brother about it. I told him how there were things in my life before that I missed: going on long walks with a dog, spending Sunday mornings or lazy evenings at the dog park. Brushing her hair, playing with her in the backyard. He astutely understood what I had missed. I didn’t miss having a dog. I missed having a dog with someone I loved. What I missed was the connection, not just the activities.

Operant conditioning is used with classical conditioning. In the case of operant conditioning, “voluntary behaviors are modified by association with the addition (or removal) of reward or aversive stimuli.” Smarter people than me recognized that behaviors (good and bad) came from “satisfying or discomforting” consequences. If you give your dog a treat every time they do something, they’ll want to do it again. If you keep listening to Japanese Breakfast’s This House on mornings when you forget to take your antidepressants, you’ll make yourself sad.

CBT isn’t perfect. People reject its problem-solving approach to therapy. I can understand where they’re coming from. I intellectualize my feelings so my past experience with therapy often involved me repeating the phrase “Intellectually, I know that, but physically I can’t get past it.” The first problem with this type of therapy is it works for a while but then can stop. The second problem is, on some level, we want to know the cause of our feelings, to explore the depths of our depression and anxiety, hopeful that in that process of discovery, we’ll find a way to overcome its associated trauma.

With strict CBT you could argue that the cause is unimportant. What matters is the active process of retraining the brain. Over time, you’ll change your brain’s pathways, building up new responses for the negative stimuli you have. In that way, the grief or trauma of your past is erased.

Though, I’m not sure if I buy that theory.

We almost didn’t get Cookie. We had to take him on a weekly trial (which is mandated by the Austin Pug Rescue, a really great organization that earnestly seems to care about placing pugs in good homes) but we couldn’t. He had some medical issues come up. We were afraid that he would come back with some big issue or diagnosis, making it harder for us to care for him.

He didn’t. Instead, he had a clean bill of health, or so we thought.

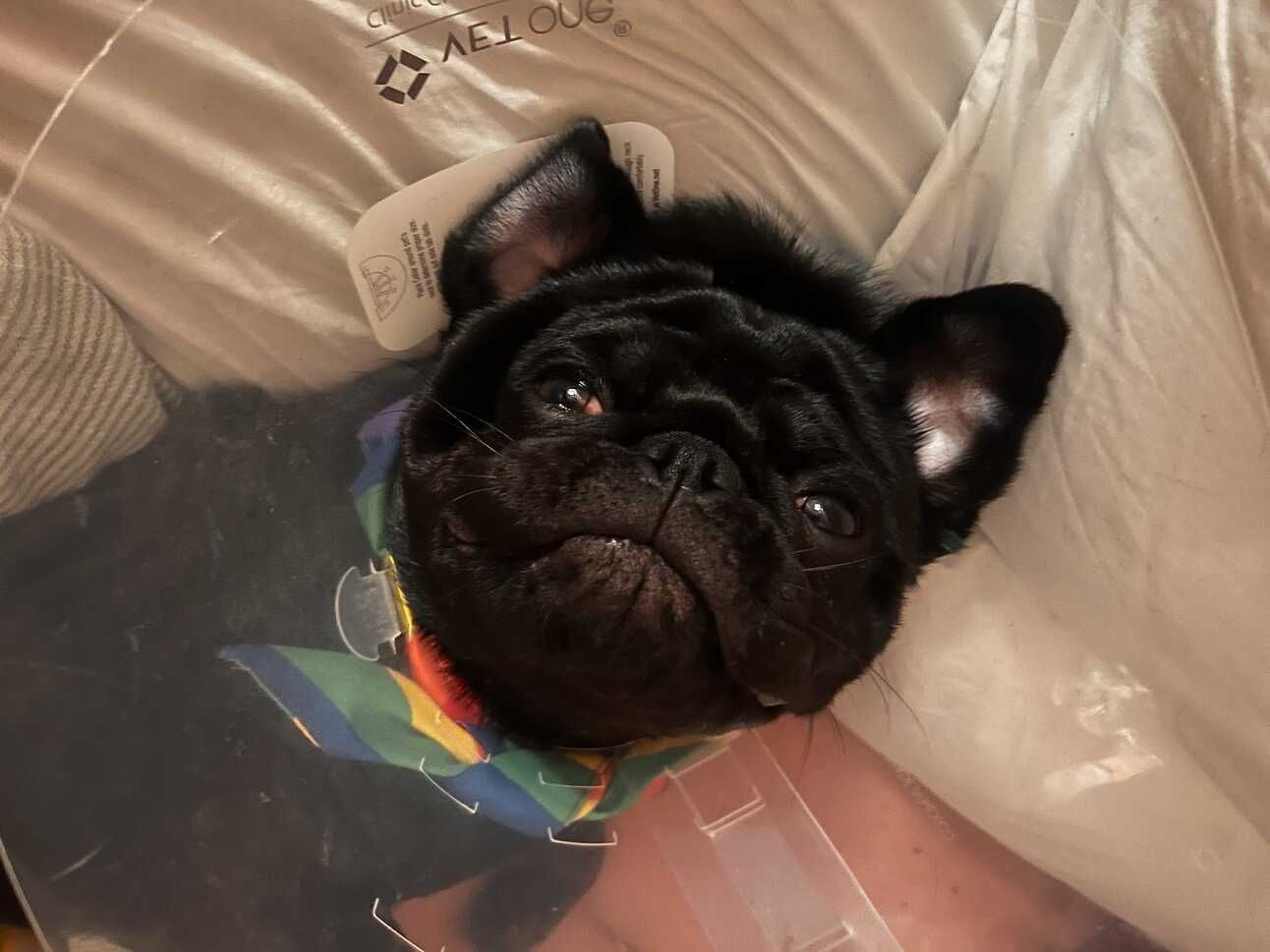

From the moment we took him home we fell in love with him. I laid with him in the back of my car, gently stroking his fur on the ride home and trying to keep him calm. A grave error as he would know be velcroed to me for the rest of his life.2 He happily played with us and licked us. He drank A LOT of water (3 bowls a day), which made us nervous. He was leaking at night and sometimes when he fell asleep on the couch. We took him to the vet and found out he had diabetes insipidus, a condition where some dogs lack the hormone necessary to regulate their water intake. They drink more and pee more because of it. He had to take three pills a day, but otherwise, he’d be fine.

The irony wasn’t lost on us: the gay couple had a dog on hormones. Take that Greg Abbot.

When I quit going to therapy, my therapist wasn't surprised. We kept going back and forth in each session, not really tackling anything new. I had all the tools available to me to make a big change in my life, what I really needed to do was just…do it.

For the first time, I could understand my depression and anxiety. I could place names to the feelings and thought patterns I had and found ways of actively shifting my focus and reorienting my life.

I was going to the gym regularly, I was hanging out with people when I needed to, I was building, moment by moment a sturdy life for myself.

Then:

A pandemic happened.

I moved apartments for the first time.

I lived alone for a year in a fancy studio apartment.

I quit my job and got a new one.

I quit that job and got a new one.

I quit that job and got a new one.

I fell in love again.

We moved in together.

We decorated an apartment and painted a wall.

We talked about getting a dog, though he wanted a pug.

I went on like that for a while before I had a horrible work experience and started slowly unraveling. I went back to therapy for a short stint, wanting to focus again on the feelings of anxiety and depression that were unspooling inside of me. I felt, naively, that I wanted to dive into the dangerous waters of my depression in hopes that I could understand its origin.

To me, my depression had always existed as this nebulous sensation. I didn’t want to kill myself, I didn’t want to die. I could get out of bed and go to work and make friends and do all the normal things people do, but still, the heavy storm of loneliness lingered over me, threatening to ruin my mood at a moment’s notice.

Going back to therapy though I felt… stifled. We spent most of our time talking about the same things we did before: conditioning the brain and using our reframing skills to change my association with my thoughts. It was nice, but I wanted something more. I stopped going. I wasn’t getting anything from it anyway.

On our walks together, I tell Zach how strange it is that Cookie is the dog we adopted. Where I’m introverted and socially awkward, Cookie is extroverted and a social expert. He knows nothing about caution or playing it cool. He runs up to people he’s never met, excited to see them. He loves to let a random stranger fill him with love.

When he plays with other dogs at the dog park he chases them around loudly yelping in excitement. In the morning when he tries to wake me up he walks over and lays down on my head. At night when we feed him dinner he jumps and barks and runs to his crate, making three big spins before proudly sitting and waiting for us to feed him.

Cookie is prone to accidents. In the year we’ve had him he’s:

Sprained a muscle from playing too hard and falling off the couch.

Broke his leg from jumping down too eagerly from the car.

Got a double ear infection.

Eaten an earring.

Exhausted himself from playing too hard in the heat.

Thrown up multiple times after playing rough with others.

Opened the hall closet while we were at the grocery store, stealing a bag of Omega-3 treats and eating half of the bag, which made him so sick that he spent the night vomiting every two hours.

Cookie is needy and playful. If he’s bored and wants attention he’ll try and bite my pants leg or nibble on my hand.3 He does this without fail once or twice a week while I’m in a meeting.4 Cookie is full of life. He is bright and happy and so thrilled to meet everyone. He barks with excited anticipation when we get near my brother and his partner’s house. He refuses to leave dog park meetups at my apartment so we have to carry him back home instead.

To me, the problem with starting therapy again was I didn’t know what I wanted. When I first went I had this clear-cut struggle before me. It was easier to proactively make a plan, and to do the work necessary to make drastic and consistent change.

But going back was different. I was incredibly anxious at work but I knew what I had to do: quit my job. Still, something was pulling me back, something lingering underneath the still waters of my anxiety, waiting to drag me under.

I understood my anxiety in this new and novel way. I got the triggers and how to unwind myself from shame spirals and catastrophic thinking. But my depression and my loneliness still lingered. I wanted to explore those feelings, but I wasn’t yet sure how to. They had always been a part of me, but were they me? Was there even a difference anyway?

In my past experiences with therapy, I did a lot of work exploring myself. Asking myself what I wanted and what type of person I wanted to be. Beyond just picking what things I enjoyed or wanted to do more of, my therapist challenged me to solidify those ideas and articulate the parts of myself that I loved or wanted to change.

What was I proud of being? What did I want to leave behind?

Cookie has taught me a lot about myself. Maybe more than going to therapy could have.

He’s taught me to be patient and less stressed, to take life a little slower, and maybe to love people unapologetically.

I say that Cookie is nothing like me, but that might not be true. Somehow, dogs always mirror their owners. My brother swears that Cookie and I have the same mustache. I think he mirrors something different: the part of me that wants to be outgoing, playful, bright, and just a little goofy. I’m not sure who’s right, but I guess I’ve still got time to figure it out.